Federica Muzzarelli, “Annemarie Schwarzenbach as a Woman Photographer and a Fashion Icon: Gender Politics and Anti-Nazi Resistance"

Abstract

This essay focuses on the existential and artistic story of Annemarie Schwarzenbach, the Swiss photographer who as a photojournalist in the early decades of the 20th century chronicled the world through a lens that, among other courageous undertakings, allowed her to document the tragic assimilation of the Nazi dictatorship in Europe. Schwarzenbach herself, however, was also the subject of many photographic portraits that friends and fellow travelers took of her. Thanks to those photographs a sort of biography in pictures has been built up over time featuring the peculiarities of an original testimony of an unconventional identity and a lesbian chic gender choice. Thus, by means of her clothes and style, photographed and thus potentially reproducible, Annemarie Schwarzenbach laid the foundations for an operation of visual concretization of her own legend, i.e., the possibility of becoming a fashion mass icon. In recent years major fashion designers have drawn on her story and those of other non-conformist and politically engaged female photographers as inspiration for their collections. As a result, they break out of elitist academic and research circles and paradoxically become pop and fashion icons. Characters digested by the glittering world of fashion, certainly generalized and simplified in meaning, but at the same time with the possibility of a spatial and temporal extension of a truly global diffusion that would otherwise be impossible to achieve. The essay is divided into three sections: the first section introduces the question of the translation made by fashion of transgressive figures transformed into fashion icons; the second and third sections focus on the relationship between Schwarzenbach and photography, and how this relationship forms the foundation for the two elements of inspiration and translation operated by pop and fashion cultures on her: gender politics and anti-Nazi resistance.

Keywords

Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Photography. Lesbo-Chic Style. Fashion and Pop Icons. Anti-Nazism. Gender Politics.

1. Photography and Mythography. From Gendered Icons to Fashion Icons

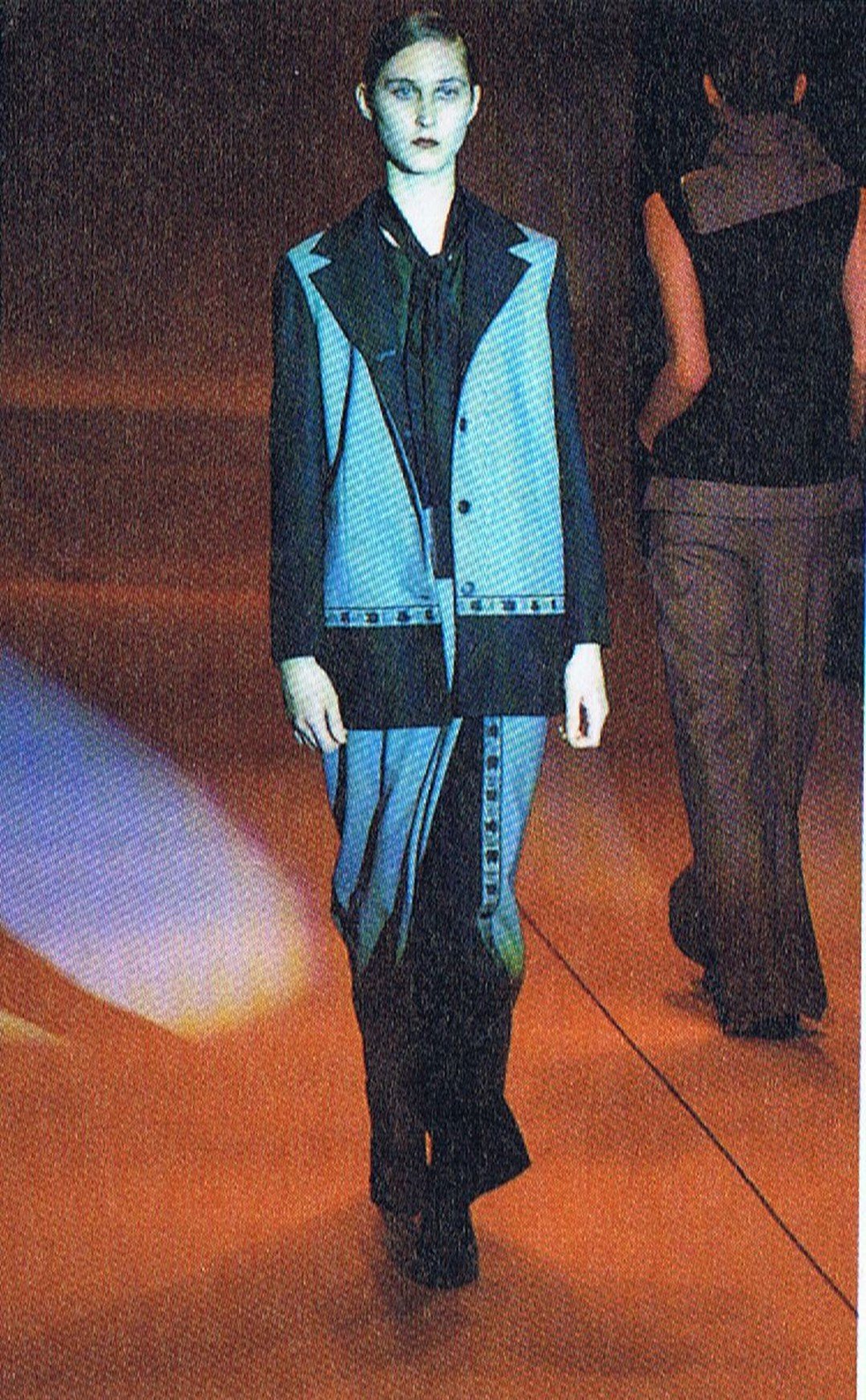

When Italian designer Antonio Marras decided to pay homage to the style of a Swiss writer and photographer named Annemarie Schwarzenbach for his first prêt-à-porter collection in fall/winter 1999-2000, the life and works of this original protagonist of early 20th-century culture was still little known. Commenting on the imagery used by Marras, the journalist Antonio Mancinelli argued that in her the Italian designer had found the dual attraction of a tormented soul, wandering both physically and in her identity: in addition to the real journey, “her figure kindled a passion for another journey, the one between the two sexes” (Mancinelli 2006)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1b

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2b

Twenty years later, for the spring/summer 2019 collection, it was the international brand of Givenchy, in the person of its artistic director Clare Waight Keller, who drew on Schwarzenbach’s fascinating, controversial history as creative inspiration:

I was researching silhouettes, and came across this spectacular looking woman, Annemarie Schwarzenbach, who dressed sometimes as a man and sometimes as a woman but always in a modest, elegant way. It spoke to me, as it aligns perfectly with what we’re doing at Givenchy. I find the idea of not being defined by a gender in the way you express yourself through clothes extremely modern. Her sense of freedom in the way she would present herself as a different character from one day to the next is highly inspiring. I also love the message about acceptance and tolerance her story gives: she was at peace with her androgyny, and so many years later, it still inspires people like me to keep on colliding codes.[1]

That is to say, what Marras and Keller considered decisive in Annemarie Schwarzenbach appears to be her ability to have been an early icon capable of interpreting instances of gender identity through choices that are both existential and related to clothing. But as will be seen below, above all Schwarzenbach played an important and original role in journalistically and photographically documenting the spread of National Socialist sentiments and the actual advent of Nazism, executing and supporting resistance and sabotage.

Quite recently, another artist and photographer who was a contemporary of Schwarzenbach, the Frenchwoman Claude Cahun, whose work was virtually unknown until the 1980s, underwent this transformation from counterculture rebel icon to pop fashion icon thanks to Maria Grazia Chiuri’s tribute for Dior. In an article online significantly titled Who was Claude Cahun, Muse of Dior’s Pre-Fall Collection? Chiuri herself explains the reasons for her fascination with Cahun:

Speaking on her decision to pick Cahun as a muse, Chiuri told Vogue, “I think in some ways [Claude Cahun] was the birth of the modern woman.” Though it’s important to question that statement by noting that Cahun did not identify as a woman – rather, they “adamantly rejected gender” altogether – Chiuri’s sentiment is still noteworthy, particularly when made on behalf of a house historically known for its rigid view of the ideal feminine silhouette.[2]

Thus, as in the collections dedicated to Schwarzenbach, Cahun’s non-conformist choices, her androgynous style, her feminism inherent in being a modern woman who also implemented forms of resistance to the prevailing heteronormative categories (in her own words, “neutral is the only gender that fits me”). And, like Schwarzenbach, Cahun’s life was marked by radical anti-Nazi political choices: isolation on the island of Jersey during the occupation of France, anti-military sabotage actions, imprisonment, a death sentence and, fortunately, liberation in April 1945.

The question one might now ask is: what do two such powerful and extreme figures, two existential adventures so limpid in their political commitment and so courageous in witnessing their diversity, have to do with the narcissistic, disengaged and superficial world of fashion and luxury?

This would obviously be a very naive question: fashion has always been, and today is more than ever, an extraordinary vehicle for disseminating content and constructing mass images. Which of course can lose something in purity and rigor when, as McLuhan taught us, they arrive encoded through the generalist message of fashion. But which precisely because of that message metabolized and remastered by the fashion system can count on such an impact and extension that perhaps only the language of music can keep up with it in terms of dissemination power. There is therefore no need to be surprised or to adopt snobbish attitudes: fashion can do a lot and the most intelligent of fashion designers are so aware of this that – like Maria Grazia Chiuri’s other openly feminist initiatives – they are increasingly promoting socially and politically committed actions that were quite unthinkable even just a few decades ago.

However, let us return to Cahun and especially Schwarzenbach, to add something about the fact that what took place in their lives was also a special synergy between their identity needs and a new cultural landscape where the emergence of a feminism that was now determined not to hide itself (where the demands of the homosexual community were included) was combined with the presence of an ideally perfect tool for recounting oneself and taking action in the world: the medium of photography. Christine Buci-Glucksmann has described this exceptional moment in an exemplary manner, a moment when dawning technological modernity was the driving force behind the cult of images and their dissemination that we are still immersed in today:

Of this we can be certain: the image engraved upon the flâneur’s body, the Baudelairean passerby barely glimpsed in the intoxication of large cities, this multiplicity of emotions are only specific examples of what is characteristic of modernity: the cult of images, the secularization/sublimation of bodies, their ephemeral nature and reproducibility (Buci-Glucksmann 1984, p. 85).

Modernity, therefore, is the fertile territory where the parallel paths of fashion and photography can create the right conditions for one of the most characterizing phenomena of our era to originate: the fashion mass icon (Muzzarelli 2022). Between the mid-19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, fashion began to acquire the physiognomy by which we understand it today: from a phenomenon that substantially distinguished high social classes to a mass phenomenon (Calefato 1996) based not only on distinction, but also on imitation permitted by the presence of technological instruments (photography and then cinema above all) capable of allowing the new taste and fashion to be conveyed, spreading far and wide.

Among those who sensed the “myth-making” power of photography, the process that Edgar Morin called “starification” (Morin 1957) and by which multiplying one’s image photographically potentially builds one’s future mass icon, making oneself eternal and identifiable forever, are Claude Cahun and Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Here the matter comes full circle when it is fashion, which has powerful channels to spread its messages, that re-appropriates distant, once marginal and avant-garde events and makes them definitive examples of pop and mass icons. On the one hand contributing to their generalist cannibalization, and on the other to the rekindling of interests beyond academic and research spheres.

2. Annemarie Schwarzenbach: The Photographic Gaze as an Existential Choice

Over the last decade, the life and work of Swiss journalist and photographer Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908-1942) have stimulated interest and fostered important studies and publications, largely thanks to the documentary and archival work of Regina Dieterle and Roger Perret, but also of Alexis Schwarzenbach’s on his family’s memories. Her unconventional and tragic biography “contributed to the shaping of Schwarzenbach into a cult figure” and built an “obsession with her biography” (Decock 2011, p. 111). Indeed, shaped by psychological torment and a countercultural lifestyle, Schwarzenbach is best known for her narrative works (novels and short stories), while the images of the numerous photojournalism projects she carried out across the world have received less critical attention. She travelled extensively in her brief arc of art and life, to the point that “unhappiness and travel became a personal program” (Georgiadou 1998, p. 117), through such regions as Asia Minor, Russia, Persia, the U.S., Germany, the Balkans, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgian Congo, and Morocco. Her literary and photographic production – quite extensive, considering her untimely death – is housed at the Swiss National Library. The scope of this essay is to investigate her choice to adopt a nonconforming attitude, which translated into radical existential and aesthetic choices, and into political resistance in the fullest sense.

Before doing so, it is important to understand why her photographic catalogue cannot be considered only as historical documentation, neutral and impassive, but rather as the bearer of an anti-dogmatic gaze, both participatory and passionate, conditioned and guided by non-heteronormative life choices and experiences of resistance.

The first challenge Annemarie Schwarzenbach had to face was the environment she was born into. Although her mother Renée (daughter of a general who commanded Swiss armed forces during WWI) cultivated openly lesbian relationship at home and in the presence of her children (first and foremost, with singer Emmy Krüger), once her daughter Annemarie began to make openly homosexual choices, a deep and irremediable divide opened between these two different incarnations of female masculinity: the one represented by a pro-Nazi aristocratic wife, and the other by a traveler anti-Nazi journalist.

The Schwarzenbach family was wealthy, tied to silk production and commerce, and politically pro-German. Rich, then, and already endowed with the ambiguous magnetism that struck everyone who met her, Annemarie enrolled at the University of Zurich (among the first of the very few women to do so at the time) to study literature. There she made the encounter that would transform her life, in an existential and political sense, in December 1930. She attended a conference delivered by Erika and Klaus Mann, the children of German writer Thomas Mann. The two young Germans became friends and role models who would profoundly mark Annemarie, for better or for worse. Erika became a pillar of anti-Nazi convictions and a guide in the common process of resistance to the unstoppable spread of fascism and its injustices across Europe (we need only recall her untiring commitment to the anti-Nazi cabaret known as Pfeffermühle). Annemarie would forever nurture a deep attraction to and love for Erika. She was bound to Klaus by friendship, cooperation, travel, and – unfortunately – the addiction to morphine and self-destructive tendencies that would drive him to suicide. It was due to a cabaret evening organized by Erika, during which a member of the powerful Schwarzenbach family was mocked, that Annemarie was forced to take sides; in aligning with the Manns, she alienated herself from her mother and family irredeemably, pursuing thereafter a life of perpetual physical and psychological nomadism. Despite this rupture, and despite the many written and visual testimonies of her opposition to the violence and aggression of German politics, Annemarie was never able to be so extreme as Erika Mann. Perhaps because of her social background, or perhaps her intellectual honesty, Schwarzenbach always sought to look at reality critically, without prejudice, seeking to understand the deep historical and social reasons for that tragedy that was about to engulf Europe and the world. She reasoned over why the Nazi ideology was able to take root in an impoverished, disillusioned cultural substratum; and how the role of intellectuals was to denounce and resist, ensuring that their work provided an outline for understanding reality and creating new awareness. This awareness probably came from the effort she applied to herself, first and foremost, to the gender identity that conflicted with the codes and stereotypes her family had established for her. Her rejection of norms, and consequent choice of a free, transgressive life, must have profoundly influenced her way of seeing the world through a photographic lens. As with other leading female figures in 18th- and 19th-century photography, for Annemarie Schwarzenbach media became a means of imprinting her autobiographical and existential choices on reality.

As mentioned above, she soon decided that the gilded life of Bocken – the Swiss town where she lived with her family under her mother’s possessive control – was not what she desired or felt suited her. After graduating from university and trying her hand at writing, she embarked on a series of long journeys that took her to far-off nations and continents, reached by driving cars thousands of kilometers through inhospitable terrain, often alone or paired with one other travel companion, at most. In 1933 she made a trip to the Pyrenees with photographer Marianne Breslauer, a student of Man Ray, who taught her the craft of photojournalism (Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 15). Writing and photography would become the two languages that enabled her to describe the world and leave a trace of her emotions and political positions. Photography also accompanied her life from another perspective: as the instrument of her visual autobiography. Indeed, Annemarie became the subject of photographic portraits by Marianne Breslauer as well as other travel and life companions. This ample collection of portraits stands as a virtual photo album that still communicates her style and visual identity. This sort of visual biography/autobiography – for it is easy to imagine that, as a photographer herself, Annemarie actively participated in the construction and portraiture choices of the friends eager to depict her – constitutes a discourse that identifies in the Swiss writer and photographer the first conspicuous example of a visual icon of the then-emerging lesbian-chic style. The twenties and thirties, when Annemarie acquired awareness of herself as an emancipated woman and lesbian, were years in which, in his analysis of the Paris of the Second Empire and the symbolic presence of female bodies in the new stage of modernity, Walter Benjamin defined the lesbian as “the heroine of modernity” (Buci-Glucksmann 1984, pp. 91-99), asserting her individual dress and visual code (Ganni, Schweppenhäuser and Tiedemann 2006, p. 168). This was the lesbian-chic dress code: masculine jackets and trousers, shirts, jumpers, unisex ties and shoes, and monocles and short hair, naturally. No makeup nor jewels. Yet this was also the dress code in which Annemarie Schwarzenbach allowed herself to be photographed for numerous portraits over a long stretch of time, so intensely as to encapsulate a very clear message: directed at the world she lived in and all those who would look, even many years later, as we do today, at her lesbian-chic style. The allure that emanated from this condition was exactly the objective that she set for herself, using photography as an eyewitness and in complicity with the women who photographed her.

Some women photographers working across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including British photographer Lady Clementina Hawarden (1822-1865), French writer and photographer Claude Cahun (pseudonym of Lucy Schwob, 1894-1954), German Dadaist Hannah Höch (1889-1978), and Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908-1942), also adopted the new technology as an opportunity to express a form of voyeuristic fetishism, visualized through cross-dressing, new dandyism, and ambiguous sexuality. Photography was an opportunity to narrate the female body and its relationship with the world, whether behind or in front of the camera. This pioneering awareness of a new aesthetic contributed to redefining artistic categories radically (Muzzarelli 2018, p. 2).

In this, Annemarie Schwarzenbach tuned in to the precise need for visibility that women of the era were demonstrating in increasingly clear ways. The new woman, the garçonne, the flapper undertook the process of female emancipation at the beginning of the 20th century by passing through a visible change in their way of dressing, accompanied by a renegotiation of gender identity that discovered in the androgynous look aesthetic terrain for new forms of resistance and political demands. The image of the new woman was a mix of criticism of the rigid, binary division of gender and of the demand for the recognition of diversity and gender-bending visibility. Clothing became a fundamental tool for defining identity, a special instrument that at once reflected and communicated the game of cross-dressing, useful for both gay self-proclamation and the heterosexual androgynous choices that characterized the first historical period of feminism. Some symbolic elements of clothing and behavior were common to both the new women and lesbian chic, including cigarettes (in 1925, French photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue dedicated a series of images to Les Femmes aux cigarettes) and monocles (symbol of the Parisian and Berlin lesbian circles of the 1920s that Brassaï portrayed in many images, including Le Monocle). Between literary characters and real lesbian-chic icons, there were many female figures who interpreted modern women and their gender issues: Victor Margueritte’s La garçonne (1922), which portrayed the newly emancipated and sexually free woman, and the protagonists of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Both published in 1928, the two novels used literary characters to render the possibility of gender fluctuations concrete. In real life, as well, some artists testified their resistance to social conventions through their conduct and visual identity: the painter Romaine Brooks (who also painted Una Troubridge, the British sculptor and writer companion of Radclyffe Hall, in boyish look,) created self-portraits in men’s clothing and employed clothing to stage her gender identity in the photographic portraits featuring her. The French writer Colette loved to dress as a man and be photographed with a cigarette trailing smoke, using all possible seductive interpretations of the homosexual aesthetic.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the choice to wear men’s clothing was, therefore, a characteristic emblem, perhaps one of the most interesting, of “something modern” (Doan 2001, p. 110). Photography was the technological medium that offered this unique period the ideal dimension for the demands that the new women who laying before the world. Photography was able to satisfy the need for the reconstitution of identity, testimony, and awareness of gender issues that was expanding in the realm of the imaginary and flight from stereotypes. “The photographic lens, more than anything, was responsible for creating a new way of seeing and a new style of beauty for women in the 20th century. The love affair between black-and-white photography and fashion is the modernist sensibility” (Wilson 1985, p. 170). Women who used the means of reproduction to disseminate and communicate their countercultural choices showed that they understood how necessary this was to implementing political choices (Muzzarelli 2009, p. 98). In particular, the doubling effected by lesbian love found in photography an instrument of insurmountable practicality and maintenance to identarian and visual reappropriation. With this choice, women refused homologation and adopted a non-heteronormative gaze, escaping the rule of being exclusive objects of male attention and voyeurism.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach was therefore not alone in her choice of portrait photography as existential, political, and identarian testimony. What distinguished her experience from others’ was this consistent, continuous submission to the camera, knowing that she was telling the story and leaving a trace of her homosexuality and the appeal that so struck those who knew her (and these certainly included Thomas Mann and Carson McCullers, the American author of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and Reflections in a Golden Eye, a novel she dedicated to Annemarie).

She had a face that I knew would haunt me to the end of my life, beautiful, blonde, with straight short hair […] She was dressed in the height of simple summer fashion, that even I could recognize as a creation of one of the great Paris couturiers (Miermont 2006, p. 235).

Photography proved a means of affirming and visualizing her gender identity as early as her frequenting of the Fetan student residence in 1925, where photo albums displayed her masculine haircut and style. Biographies also record that her photographs were the object of a fetishistic cult among her female classmates; when her first novel, Freunde um Bernhard, came out, someone broke the window of the bookshop where a copy of the book was on display just to obtain the photographic portrait of her that the publisher Amalthea had chosen for the cover. “There is in Annemarie a subversive charge, a disturbing anomaly that makes her an icon with an unforgettable face to this day” (Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 19). Marianne Breslauer, to whom we owe most of her portraits, photographed her during her stay in Berlin from 1931-1932: Annemarie was completely engrossed in the nightlife of the German capital, frequenting the gay clubs where her lesbian-chic style met with great success. She dressed with extreme elegance, in masculine jackets and unbuttoned white shirts.

In Schwarzenbach’s case, both her life and media image offered a testimony of a photographic practice identified by some pioneering interpreters of this shared poetics – see Cahun and Höch – as being most suited to interpreting instances of identity construction and the display of different styles from the accepted norm. Having lived in Paris and Berlin, two of the capitals where the lesbian subculture emerged in the 1920s, Schwarzenbach was capable of transposing these new demands for visibility and recognition into her adopted style, later documented through photography. Particularly in Berlin, she discovered the lesbian clubs around Nollendorf Square, like Maly und Igel, where her men’s shirts and her garçonne haircut were greatly appreciated (Muzzarelli 2018, pp. 10-11).

During a 1932 trip to Venice with Erika and Klaus Mann, she chose to be photographed in men’s clothing, smoking a cigarette, or wearing a swimming costume to flaunt her ephebic body and intriguing sexuality. Another aspect of her life was also much-photographed: her encounters with Claude Clarac, second secretary at the French embassy in Persia and a homosexual like Annemarie, whom she married, obtaining a diplomatic passport. She likely experienced some interludes of her life with this refined man, though always punctuated by hospitalization due to drug addiction and suicide attempts. In some of the photos taken during their travels, even in the company of friends, Annemarie is always photographed in her androgynous, sporty style, to the extent that the couple appears to dress identically. The photographs testify to desert crossings, hunting trips, dips in the pool, visits to archaeological digs: in all of them, she represented herself as an androgynous chic lesbian. “From her slender body, from her pensive face, illuminated by the pallor of her forehead, she exuded an allure that infallibly acted on those who feel attracted to the tragic grandeur of the androgynous” (Maillart 1987). What is striking is that her allure did not diminish, and perhaps even increased, when the signs of physical and psychological suffering were visible on her face, or even when her wrists were bandaged, as after a stay in a Samedan clinic in 1935. Although she was always very elegant, the dark circles under her eyes became more and more evident in photographs, contrasting with the childlike air of her face. “Chic, dressed in grey, so thin as to be almost ethereal”: with these words Ella Maillart, the famous travel writer, described her during their first meeting in Zurich before her departure for Prague (Maillart 1987, p. 81). The two women continued to write to each other and finally decided to embark on a journey, financed by magazines and publishers interested in their writing and photography, from Afghanistan to India. For Maillart, the trip was an important experience (she enjoyed a lengthy stay in an Indian ashram). For Annemarie, however, it concluded early: she returned to Europe in January 1940, suffocated and pursued by disease and mental instability (Georgiadou 1998, p. 175).

Two years of departures (the USA, the Congo) and return trips followed. Of sufferings and utopian impulses. Her photographs are what she left behind, to tell the story of herself and the world she could see.

You should only live with questions and restlessness; that is the best part of you. I would like you to remain forever thus, ready to blossom; you should not submit so easily to a law, nor rest on what already exists. You should never feel completely satisfied (Ruina 2015).

3. Anti-Nazism as a Photographic Practice and a Political Choice

Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s entire photographic production, the images she brought back from her adventurous and demanding journeys to the two ends of the world, still stand today as the special visual testimony of a woman whose view was neither stereotyped nor codified. The many photographs with which she recounted non-western peoples, customs, and behaviors were complementary to the many newspaper articles and prose compositions that grew out of the same nomadic experiences. The drive for social, cultural, and political narratives, which will be discussed in a moment, and the value of the photographic act as an exercise in mediation with the world coexisted in this oeuvre: for her, photography was a way of establishing empathetic contact with things and people, a dimension that was always a source of great distress during her brief existence.

The Middle East would become the place par excellence for her to confront herself and the world. Here, where the history of European culture begins, she celebrated her separation from Europe. Annemarie Schwarzenbach was soon no longer a mere traveler to Persia, not just a visitor, but a woman who reflected upon and mourned the downfall of her native continent in the country’s vast expanses and deserts. The Persian mountains were the grand backdrop for her lack of a homeland, and her uprootedness. These feelings of estrangement dominated even her journalistic accounts of the East (Georgiadou 1998, p. 116). It should be remembered how other women, special women, had already used photography throughout the 19th century to assert their identity, autonomy, and professionalism in the field of journalism, especially in America. The pioneering examples of Benjamin Frances Johnson and Alice Austen, followed by Marion Post Wolcott and Dorothea Lange, are worth mentioning. But other great pioneers of photojournalism brought the female gaze to this decidedly masculine environment in the same years as Schwarzenbach: in Europe, the wartime activity of Gerda Taro in Spain and Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White in the territories devastated by Nazi ferocity are worth recalling (Sullivan 1994; Lebart and Robert 2020). Having established that, the Swiss photographer’s contribution to the imaginal description of a part of the world undergoing a transformation under the Nazi aegis will be explored here. One characteristic of her poetics was how her photographic eye did not dwell only on the imposing parades and other striking aspects ushered in by Nazism. Indeed, she was often attracted to unique and small things: anonymous details that often represented the most incisive evidence of revolutionized daily life. In this, too, she enacted resistance that was perhaps less ideological but very transparent and honest. She let objects and people speak for themselves, allowing the monstrosity of what was happening to reveal itself naturally through photography. Indeed, as Leena Eilittä underlines “despite the apparent neutrality of Shwarzenbach’s reports, there is no doubt about her critical attitude toward the spread of National Socialism which also reflect the expectations of the majority of her Swiss readers” (Eilittä 2010, p. 102). Moreover, and a closer reading, both her photographs and her reports, through an apparently neutral style, convey her criticism and resistance towards the spread of National Socialism in Europe, thanks to the capacity of focusing her lens on grotesque details of expressions, behaviors and clothing especially of young people (Eilittä 2010, pp. 105-106).

Of her vast photographic oeuvre, her 1937-1938 journeys bore witness to an aversion to the progressive expansion of Nazi occupation and, at the same time, demonstrated her ability to seek out a non-trivial and non-stereotypical explanation in social and cultural environments for the surge that was about to devastate the world. As discussed above, her work always intertwined photography and writing. She carried them out as complementary and homologous actions. Her articles and photo stories were lucid, tragic descriptions of the events she witnessed, leaving no doubt of her anti-Nazi position. They were always accompanied by an attempt to overcome appearances and facile conclusions and discern the mechanisms underlying a madness that was—and one must always remember this—aided, abetted, and hailed enthusiastically by so many. As mentioned above, Annemarie took a public stand against her family’s pro-Nazi tendencies (in particular, that of her uncle Ulrich Wille, a colonel in the army corps). She had to accept the painful hypocrisy of Switzerland’s policy of neutrality, going so far as to define it, in the title of one article, “the country that never fired a single shot” (Georgiadou 1998, pp. 74-75). Upon returning from her first trip to the U.S. in 1937 and delivering a radio lecture on the prospects of democracy in America, she set off by train to see for herself the impact of the Reich’s advance in Germany, Poland, and the Baltic States. Arriving in Gdansk (Guernica had recently been bombed), she was shocked to find a city completely decked out in flags in honor of Goebbels, who was visiting to attend the Congress of Culture.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3b

“The next day, I learned the cultural congress’s schedule from the hotel porter: SA (assault units) parade, SS (protective militia) parade, HJ (Hitler Youth) parade, BDM (Hitler Girls’ Organisation) parade, and the parade of the Arbeitsdienstler, the compulsory labor service” (Schwarzenbach, “Conference of Culture,” in Brief Encounters in Germany, a 1937 typescript, reprinted in Dieterle and Perret 2001, pp. 118-119). She wrote of the staging of Don Carlos at the Civic Theatre in honor of Goebbels, “At this very moment, there in the theatre, the Marquis of Posa is uttering the most beautiful words Schiller ever wrote about freedom” (2001, p. 120). In the streets, Annemarie photographed buildings covered with flags bearing hooked crosses, shop windows displaying Nazi symbols, jubilant groups of Hitler Youth, and boys and girls parading or proudly displaying their Nazi uniforms.

Fig. 4a

Fig. 4b

She often wrote annotations, long captions, and legends on the photographs (there are negatives and positives in the collection, but not always both). In one photo, a small symbol can be glimpsed in the corner of a windowpane. The annotation specifies that the window was located in a small fishing village outside Gdansk and that the symbol was typically found in the windows of large shops in the city: save for those run by Jews. Already, the eagerness to declare oneself Aryan had contaminated everyone.

Fig. 5a

Fig. 5b

In another image of Gdansk, Annemarie noted that the signs outside of public buildings denounced the true condition of a city that was no longer free: she underlined how the German Nazi Party exercised the main role in civic politics and “Forster is the leader of the Nazis in Danzig, being the real ruler of the ‘Free Town’.” The same logic applied to photos of newsstands and columns of posted notices in which, she argued, it was clear that Nazi censorship was at work as no newspaper or magazine unaligned with Third Reich policy was ever sold or posted. The information embargo had clearly penetrated even “free” Gdansk.

Fig. 6a

Fig. 6b

In the typescript entitled “Brief Encounters in Germany,” she wrote: “I would simply like to relate what I have heard here and there from the common man. Mine, therefore, is not intended to be a critical analysis of events and the situation, of certain principles and their consequences within the Third Reich. To do this one would need to critically examine and compare the statements I have collected.” With the aim of reporting on the dramatic situation and exasperation of the workers she interviewed, Schwarzenbach then compiled a precise list of everything one would need to listen to, read, and understand in order to really form an opinion on what was being discussed: statistics, trade regulations, criticism of the policies of national governments. She meant that this was not always the case in the day-to-day craft of journalism: an admission that not everyone would be willing to make, then or now. She observed that “the Jewish timber merchant, travelling salesman, and farmer all have a right to be heard. From their voices and that of their Volksgenossen, what any democracy calls ‘public opinion’ is born. It should not be forgotten that despite the levelling of social life and oppression, these voices exist even in the Third Reich and will one day be heard loud and clear” (Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 117). She did not hesitate to place herself at risk and enter a club near the railway station – known as a hangout for “suspicious persons” – to try to meet the people of Gdansk. Yet she also asked himself if “seventeen-year-old girls, schoolgirls, and housewives are all ‘politically educated’,” is it possible they cannot keep even a corner of their soul intact […]?” (2001, p. 128). Annemarie then continued on to the Baltic countries (Riga, Tallinn) arriving in Moscow at the end of May. In “Beyond the Corridor” (in Baltic Diary, a 1937 typescript, published in two magazines that same year), she wrote that “since I left Gdansk, I have continued seeing flags with the hooked cross, white banners with election inscriptions and slogans, processions of children in uniform, the typical bustle of SA men in small cafés” (2001, p. 132). In Kaunas, “nationalism borders on nationalist arrogance. […] In Lithuania, people are exceedingly xenophobic, and not only towards Germans. […] The hatred is directed above all against the minorities living in Lithuania, including the Jews” (Kaunas was the capital of the “first generation” in Baltic Diary, typescript published in a magazine: 2001, p. 137).

In the autumn of 1937, Annemarie returned to the USA for the second time, accompanied by Barbara Hamilton-Wright. They travelled through a number of southern states. During this short but intense period, she wrote and photographed extensively, denouncing the racist and violent positions of the Ku Klux Klan from a point of view that Thomas Mann described as “extremely socialist and sympathetic to Roosevelt” (Letter of 25 August 1938 to Ferdinand Lion; reproduced in Miermont 2004, p. 182). Although not the specific subject of this essay, it is worth noting that Schwarzenbach portrayed the misery and poverty shared by many sharecroppers and workers so powerfully in her photographic work during this trip that its visual impact was comparable only to that of the FSA photography campaign of the same period, which other great photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Marion Post Wolcott contributed to, although she was distinguished from them in working on commission. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was a government agency planned by Franklin Roosevelt since 1935 with the aim of documenting, through pictures, the miserable situation of people caused by the Depression era. The American experience was a crucial stage for Schwarzenbach from a stylistic point of view: she embarked upon social and documentary photography thanks to the direct access to FSA archives that Director Stryker had granted her (Georgiadou 1998, p. 155). Above all, it raised her awareness of how photography could serve as an instrument of politics and resistance. Yet even in a context so fraught with sentimentality and demagogy, she maintained her unfailing critical spirit and intellectual honesty, wondering to what extent a photograph could really change the lives of the downtrodden (“Lumberton. Notes,” in Perret 2004, p. 116). Thanks to this fundamental experience, more and more involved in the Jewish and resistance cause, both her photographic gaze and her writing evolved to become drier and more objective, and in doing so more capable of visualizing the violence atmosphere for which the Nazis were responsible.

Fig. 7a

Fig. 7b

The Europe that Annemarie returned home to in February 1938, together with Klaus Mann, was now in an unstoppable race towards grim Nazi domination. On March 12, 1938, the Anschluss handed Austria over to the Reich. A few days later, the Swiss photojournalist crossed the border into Austria on a ‘secret mission’ which was a sort of tribute to her friendship with the Mann siblings. She plotted with them to help a mutual friend, Magnus Henning (pianist and co-founder of the Pfeffermühle), escape, as well as to seek contacts among the Austrian resistance and German refugees. During her journey by car to Vienna, through Innsbruck, Kitzbühel, and Salzburg, she was horrified by what she witnessed: the country was all but besieged, with troops everywhere, hotel rooms impossible to find, and Nazi uniforms on parade (Figure 9). She wrote of her visit to Landegg that “the whole town has turned into a garrison; trucks, tanks, and motorized field artillery are constantly streaming down the Arlberg pass” (“Austria has changed radically,” 1938 typescript, in Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 197). In Salzburg, “you see sentries with steel helmets and erect bayonets. […] And in the square (named for) Adolf Hitler, columns of young Nazis march. They still wear the green tunics and white wool stockings of regional costume, but discipline, obedience, and even panic have already hardened the features of their young faces.” (2001, p. 198). But she also saw the ranks of unemployed who received benefits from the German militia.

She described the rows of Jews forced by the Brownshirts to sweep the streets and clean the barrack latrines. In Vienna, Hitler’s face hung on walls and small swastika flags hang or fluttered on the roadside, ready to be hoisted. And when she took photos of the SS men, she is successful in “Introducing a striking contrast” between “the guilty of the SS men and the ongoing political misery that was about to destroy the valuable cultural traditions of Vienna (Elittä 2010, p. 111). No doubt at great risk, Annemarie sought to make contact with the local population, ask questions, and engage in conversation, hoping to gain useful information. In particular, she visited the Ottakring district, where Dollfuss had opened fire on the communists in 1934. She entered a tavern bearing the inscription “Guaranteed German, Aryan house. Exclusively Aryan service,” ordered a beer, and asked questions about the Nazis to try to gauge the reaction of some of the waitresses and understand their thinking. She also had a list of addresses to visit in order to build bridges between the resistance and refugees (the addresses were printed on celluloid sheets so as to be easily erased should she be stopped at a Nazi checkpoint). In a posthumously published article entitled “Mass Arrests among Austrian Officers. Nationalism without a Mask,” she recounted two unsuccessful missions. In one case, the revolutionary socialist she was to talk to had already been arrested by the SS (Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 200). In the other, she learned more about the driving forces allowing Nazi expansion to take root. The man she spoke to, of whom she had requested information to report to a comrade in Switzerland, replied:

Comrade. Comrades no longer exist. You have to adapt […] I had been unemployed since 1934. I was a tram driver. Under the ‘black government’ I was an outcast. Now I have my job back. My wife […] is leaving tomorrow on a Kraft durch Freude train for Munich. Holidays, a nice trip, all paid for. The only condition is that I cut off relations with my old comrades (Schwarzenbach 1938).

Thanks to her diplomatic passport, Annemarie was able to help several Austrian antifascists escape to Switzerland. Yet once back in Switzerland, she fell into the crisis of drug addiction and yet another admission to the Samedan clinic. However, the more she felt her strength failing, the clearer it became that the antifascist resistance was the main objective of her life and work.

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8b

On 19 September 1938, she took a plane to Prague, then under tremendous pressure as the Third Reich, having annexed Austria, was eager to take over the Sudetenland. Annemarie was part of a contingent of international journalists stationed at the Ambassador Hotel. Her support for Czechoslovakia, in opposition to Hitler’s policy, was clearly expressed in an article in which she condemned “the monstrous and indecent way in which the art of lying, the alteration of the truth and the pure invention of facts is practiced” (“Involuntary Strike of the Prague Correspondents,” a 1938 article published posthumously in Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 218). Communications were cut off and the journalists trapped without external contact for 48 hours. By then, the situation was out of control; even the electricity was cut off: “No, Prague was cut off from the world. Only the official state lines worked: in London, Paris, New York, Bern, Stockholm, you only found out from the official radio what was happening that night in the heart and crux of Europe” (Dieterle and Perret 2001, p. 219). A few days later, she boarded a Swissair flight for the repatriation of Swiss journalists. Though the mission was quite brief, Annemarie managed nonetheless to write a number of articles and take numerous photos. Among the most disturbing are those in which she captures families of women and children with bundles on their shoulders, trying to escape the horror.

Then there were the refugees the Red Cross and communist organization Solidarity tried to shelter. The start of the war was now very close. Annemarie Schwarzenbach returned to the manuscript she had abandoned, Death in Persia, the new version of which she entitled The Happy Valley. She then managed to make a series of challenging journeys, including one with Ella Maillart through Persia to India, then the USA, and finally the Congo and Morocco. She also planned to join de Gaulle’s Resistance forces. He died in a stupid way, falling off her bicycle, probably due to the fragility of her exhausted body. The chasm between Annemarie Schwarzenbach and her mother could not be bridged even after her death, when her mother and grandmother (a direct relation of Chancellor von Bismarck) ignored her wishes and destroyed documents and letters that might embarrass the family. Although her will was not honored, with her diaries, correspondence, and compositions all destroyed, her work and testimony nevertheless survive at the SNL in Bern. Her literary, journalistic, and photographic endeavors provide one of the most interesting examples of a woman in a world in crisis: mirroring the crisis she suffered in her personal life, which despite the tragic nature of her existence and the times she lived in, she was able to interpret with the courage to adopt a different outlook, a lucid position of resistance, and nonnormative perspective.

[1] See https://www.anothermanmag.com/style-grooming/10806/annemarie-schwarzenbach-clare-waight-keller-interview-givenchy-ss19-muse.

[2] See https://www.vogue.com/article/claude-cahun-gender-muse-pre-fall-2018-christian-dior.

Bibliography

AA.VV. Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Roma: In Immagini e Parole, 2016.

Barthes, R. Le Mythe du dandy, ed. E. Carassus. Paris: Armond Colin, 1971.

Blessing, J. Rrose is a rrose is a rrose: Gender Performance in Photography. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1997.

Bouveresse, C. Les femmes photographes. Paris: Actes Sud, 2020.

Brettle, J. and Rice, S. Public Bodies-Private States: New Views on Photography, Representation and Gender. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Broude, N. and Garrard, M.G. Reclaiming Female Agency. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

Buci-Glucksmann, C. La raison barocque. De Baudelaire à Benjamin. Paris: Galilée, 1984.

Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of the Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Butler, J. Bodies that Matter: On the Discoursive Limits of Sex. London: Routledge, 1993.

Calefato, P. Mass moda. Linguaggio e immaginario del corpo rivestito. Genova: Costa and Nolan, 1996.

Carbone, M. “Einletung.” In Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Werk, Wirkung, Kontex. Akten der Tagung in Sils-Engadin. Oktober 2008, 9-19. Bielefeld: Aisthesis Verlag, 2010.

Carstarphen, M.G. and Zavoina, S.C. Sexual Rhetoric: Media Perspectives on Sexuality, Gender, and Identity. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999.

Chadwick, W. Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson, 1990.

Chadwick, W. The Modern Woman Revisited: Paris Between the Wars. New Brunswick (NJ)-London: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Cogeval, G. Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839-1945. Paris: Hazan, 2015.

Cottingham, L. Lesbians Are So Chic… That We’re Not Real Lesbians at All. London: Cassell, 1996.

Crane, D. Fashion and its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in Clothing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

De Beauvoir, S. Le deuxième sexe. Paris: Gallimard, 1949.

Decock, S. “‘The loving conquest and embrace’: On peaceful heterotopias and utopias in Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s Asian and Africa travel writings.” Women in German Yearbook 2011, vol. 27, 109-130. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Dewey, J. Art as Experience. New York: The Berkley Publishing Group, 1934.

Dews, C.L. Ed. Illumination and Night Glare. The Unfinished Autobiography of Carson McCullers. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

Dieterle, R. “Annemarie Schwarzenbach: Swiss Photo-journalist of the 1930s’.” History of Photography 2, 3 (1998): 223-228.

Dieterle, R. and Perret, R. Eds. Auf der Schattenseite. Basel: Lenos Verlag, 1990 (Italian transl. Dalla parte dell’ombra. Milano: il Saggiatore, 2001).

Doan, L. Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of Modern English Lesbian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Doy, G. Claude Cahun. A Sensual Politics of Photography. New York-London: I.B. Tauris, 2007.

Dubois, P. L’acte photographique. Paris-Bruxelles: Nathan-Labor, 1983.

Eilittä, L. “‘This can only come to a bad end’: Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s critique of National Socialism in her reports and photography from Europe.” Women in German Yearbook 2010, vol. 26, 1, 97-116. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Fillin-Yeh, S. Ed. Dandies. Fashion and Finesse in Art and Culture. New York-London: New York University Press, 2001.

Forte, J. “Women’s Performance Art: Feminism and Postmodernism.” Theatre Journal 40, 2 (May 1988): 217-235.

Fraser, H. and White, R.S. Constructing Gender: Feminism in Literary Studies. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press, 1994.

Friedewald, B. Women Photographers from Julia Margaret Cameron to Cindy Sherman. Münich-London-New York: Prestel, 2014.

Ganni, E., Schweppenhäuser, H. and Tiedemann, R. Ed. Walter Benjamin. Opere complete. Scritti 1938-1940. Tomo 3. Torino: Einaudi, 2006.

Garber, M. Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing & Cultural Anxiety. New York-London: Routledge, 1992.

Georgiadou, A. Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Das Leben zerfetzt sich mir in tausend Stücke. Biographie. Frankfurt a.M.-New York: Campus Verlag, 1995 (Italian transl. La vita in pezzi. Una biografia di Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Ferrara: Tufani, 1998).

Glick, E. “The Dialectics of Dandyism.” Cultural Critique 48, 1 (2001): 129-163.

Gonnard, C. and Lebovici, É. Femmes Artistes/Artistes Femmes: Paris, de 1880 à nos jours. Paris: Hazan, 2007.

Halberstam, J. Female Masculinity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1998.

Heller, D. Cross-Purposes. Lesbians, Feminist, and the Limits of Alliance. Bloomington-Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Hollander, A. Sex and Suits. The Evolution in Modern Dress. New York: Kodansha, 1994.

Hsiao-yen, P. Dandyism and Transcultural Modernity. London-New York: Routledge, 2010.

Kasindorf, J.R. “Lesbian Chic.” New York 19, 6 (1993): 30-37.

Jones, A. The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. London: Routledge, 2003.

Lavizzari, A. Fast eine Liebe: Annemarie Schwarzenbach und Carson McCullers. Auflage-Open Library, 2008.

Lebart, L. and Robert, M. Une histoire mondiale des femmes photographes. Paris: Les Éditions Textuel, 2020.

Leperlier, F. Ed. Claude Cahun photographe: 1894-1954. Paris: Jean-Michael Place – Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1995.

Lewinsky, M. and Bigini, A. Ella Maillart. Double Journey. Docufilm: Cineteca di Bologna, 2015.

Maillart, E. The Cruel Way (1948). London: Virago-Beacon Travelers, 1993.

Mancinelli, A. Antonio Marras. Venice: Marsilio, 2006.

Mann, K. The turning point. Autobiography of Klaus Mann (1942). Princeton (NJ): Markus Wiener Publishers, 1995.

McCann, C.R. and Kim, S.-K. Feminist Theory Reader. Local and Global Perspective. London-New York: Routledge, 2003.

Mesh, R. Before Trans. Three Gender Stories form Nineteenth-Century France. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2020.

Miermont, D.L. Annemarie Schwarzenbach ou le mal d’Europe. Paris: Payot et Rivages, 2004 (Italian transl. Una terribile libertà. Ritratto di Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Milano: il Saggiatore, 2006).

Morand, P. Journal d’un attaché d’ambassade, 1916-1917. Paris: Gallimard, 1996.

Morin, E. Les Stars. Paris: Édition du Seuil, 1957.

Müller, D. L’Ange inconsolable. Une biographie d’Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Toulous: Lieu Commun, 1989.

Muzzarelli, F. Femmes Photographes. Émancipation et Performance (1850-1940). Paris: Hazan, 2009.

Muzzarelli, F. “Women Photographers and Female Identities: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, New Dandy and Lesbian Chic Icon.” Visual Resources 34 (2018): 1-28.

Muzzarelli, F. Photography and Modern Icons. The Visual Planning of Myth. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022.

Newton, E. “The Mythic Mannish Lesbian: Radclyffe Hall and the New Woman”, Signs 9, 4 (1984): 557-575.

Perret, R. Ed. Annemarie Schwarzenbac. Basel: Lenos Verlag, 2000.

Perret, R. Jenseits von New York. Basel: Lenos Verlag, 1992 (Italian transl. Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Oltre New York. Reportage e Fotografie 1936-1938. Milano: il Saggiatore, 2004).

Pykett, L. The “improper” Feminine: The Women Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing. London-New York: Routledge, 1992.

Pollock, G. Vision and Difference. Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art. London-New York: Routledge, 1988.

Raymond, C. Women photographers and Feminist Aesthetics. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Reckitt, H. Art and Feminism. London: Phaidon, 2001.

Reichert, T. “Lesbian Chic Imagery in Advertising: Interpretations and Insight of Female Same-Sex Eroticism.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 23, 2 (2001): 9-22.

Robinson, H. Feminism Art Theory: An Anthology, 1968-2000. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

Rosemblum, N. A History of Women Photographers. New York: Abbeville Press, 1994.

Ruina, F. “Annemarie Schwarzenbach: dalla parte dell’ombra.” Doppiozero (9 December 2015), available at: https://www.doppiozero.com/materiali/parole/annemarie-schwarzenbach-dalla-parte-dellombra (last accessed: 17 May 2021).

Sandweiss, M.A., Lahs, Gonzales O. and Lippard, L. Eds. Defining Eye/Defining I. Women Photographers of the 20th Century. Cat. of the St. Louis Art Museum, 1997.

Shapland, J. My Autobiography of Curson McCullers. Boston: Little Browne Book Group, 2021.

Schwarzenbach, A. Auf der Schwelle des Fremden: Das Leben der Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Münich: Collection Rolf Heyne, 2008.

Schwarzenbach, A. “Maman, tu dois lire mon livre.” Annemarie Schwarzenbach, sa mère et sa grand-mère. Geneva: Editions Métropolis, 2007.

Schwarzenbach, A. “Die Steppe.” National Zeitung 508 (1939).

Schwarzenbach, A. Winter in Vorderasien. Basel: Lenos, 2002 (1934).

Schwarzenbach, A. Eine Frau Zu Sehen, ed. A. Schwarzenbach. Zurich: Kein & Aber, 2008 (French edition Voir une femme. Genève: Metropolis, 2008).

Schwarzenbach, A. All the Roads are open. The Afghan Journey, ed. R. Perret. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011 (2000).

Schwarzenbach, A. Death in Persia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013 (1995).

Smith, S. and Watson, J. Interfaces. Women/Autobiography/Image/Performance. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Smith, S. Women’s Autobiographical Practises in the Twentieth Century. Indianapolis-Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Sullivan, C. Women Photographers. London: Virago Press, 1990.

True Latimer, T. Women Together/Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris. New Brunswick (NJ)-London: Rutgers University Press, 2005.

Von Ankum, K. Women in the Metropolis. Gender and Modernity in Weimar Culture. Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997.

Walker, L.M. “How to Recognize a Lesbian: The Cultural Politics of Looking like What You Are.” Sign. Journal of Women Culture and Society 18, 4 (1993): 866-890.

Wilson, E. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. London: Virago, 1985.

Zimmermann, B. Ed. Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia. London-New York: Taylor & Francis, 2000.

Woodward, K. Ed. Identity and Difference. Culture, Media, and Identities. London: Sage, 1997.

List of Figures

Figure 1: Antonio Marras, Prêt-à-porter collection, fall/winter 1999/2000; ©Antonio Marras

Figure 2: Antonio Marras, Prêt-à-porter collection, fall/winter 1999/2000; ©Antonio Marras

Figure 3: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Bund Deutscher Mädel, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-033; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Bund_Deutscher_Mädel_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-033.jpg)

+ : Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Gebäude, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-043; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Gebäude_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-043.jpg)

Figure 4: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Hitlerjugend, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-062; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Hitlerjugend_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-062.jpg)

+ Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Hitlerjugend, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-072; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Hitlerjugend_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-072.jpg)

Figure 5: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Zeitungsstand, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-060; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Zeitungsstand_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-060.jpg).

+ Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Fenster, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-080; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Fenster_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-080.jpg)

Figure 6: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Schilder (NSDAP), 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-057; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Schilder_(NSDAP)_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-057.jpg)

+ Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Freie Stadt Danzig, Gdansk, Plakatsäule, 1937

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-059; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Freie_Stadt_Danzig,_Danzig_(Gdansk)-_Plakatsäule_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-13-059.jpg)

Figure 7: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Österreich, Salzburg, Menschen, 1938

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach- A-5-18-026; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Österreich,_Salzburg-_Menschen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-18-026.jpg)

+ Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Österreich, Salzburg, Menschen, 1938

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach- A-5-18-029; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Österreich,_Salzburg-_Menschen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-18-029.jpg)

Figure 8: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Tschechoslowakei, Prague, Menschen, 1938

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach- A-5-18-086; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Tschechoslowakei,_Prag_(Praha)-_Menschen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-18-086.jpg

+ Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Tschechoslowakei, Prague, Menschen, 1938

(Image courtesy: Swiss National Library, SLA-Schwarzenbach- A-5-18-095; Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CH-NB_-_Tschechoslowakei,_Prag_(Praha)-_Menschen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-18-095.jpg).

Websites

https://www.anothermanmag.com/style-grooming/10806/annemarie-schwarzenbach-clare-waight-keller-interview-givenchy-ss19-muse.

https://www.vogue.com/article/claude-cahun-gender-muse-pre-fall-2018-christian-dior.